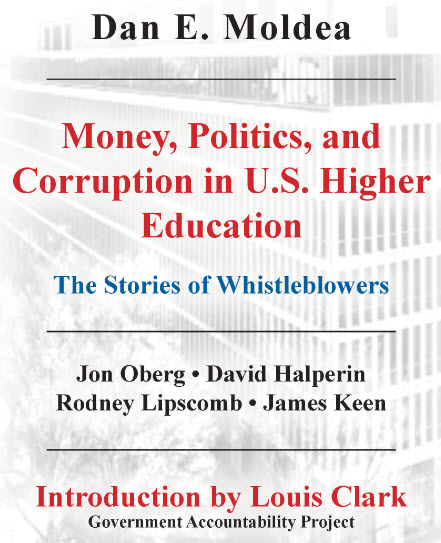

MONEY, POLITICS, AND

CORRUPTION

IN U.S. HIGHER EDUCATION

The Stories of Whistleblowers

By Dan E. Moldea

INTRODUCTION

By Louis Clark

Executive Director and CEO,

Government Accountability Project

After years of

lecturing about whistleblowing on college campuses and at many

other venues

across the country, I have heard every conceivable question on

the subject of

whistleblowers. The

one question that

students, professors, and members of the public alike have

asked more

frequently than any other is:

“Who are

these people who blow the whistle?” IN U.S. HIGHER EDUCATION

The Stories of Whistleblowers

By Dan E. Moldea

INTRODUCTION

By Louis Clark

Executive Director and CEO,

Government Accountability Project

Like Dan Moldea, the author of this book, I often look to whistleblowers themselves to answer this question. On the occasions when I am fortunate to be sharing the stage with such notable whistleblowers as Dr. Daniel Ellsberg, Coleen Rowley, Thomas Drake, Sherron Watkins, Frank Serpico, Dr. Susan Wood, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, and Dr. Jon Oberg, all I need do is keep quiet and let them speak. These whistleblowers enthrall, inspire, and inform the understanding of each and every audience they address.

It is fitting that Moldea has chosen to keep whistleblowers’ identities at the forefront of his readers’ minds in this ground-breaking new book. I have known Dan since we met more than forty years ago at the influential Institute for Policy Studies. He was already working his way toward becoming one of Washington’s most courageous investigative reporters, and I had just helped found the Government Accountability Project, a whistleblower-support organization.

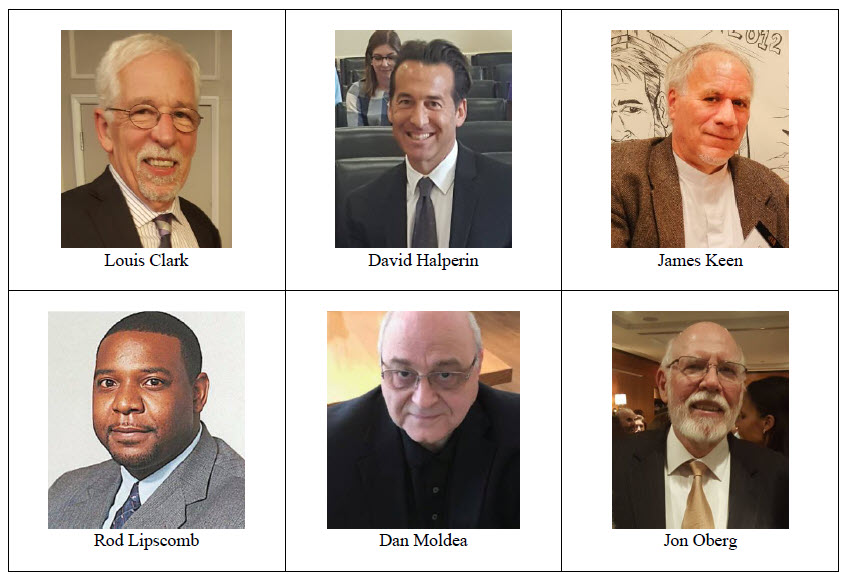

In his book, Moldea foregrounds the question of “Who is a whistleblower?” Moldea focuses on three whistleblowers: Dr. Jon Oberg, Rod Lipscomb, and Dr. Jim Keen, as well as attorney David Halperin, a well-known and respected advocate of whistleblowers. Moldea traces the origins of the complex scandals that these whistleblowers exposed, identifies the allies and enemies they attracted, and illuminates the retaliation they have courageously endured. From these case studies, a powerful narrative emerges: Moldea shows his readers what happens when good people decide not to remain silent when confronted with rampant corruption in higher education.

It is noteworthy that Moldea has now turned his attention to the once hallowed halls of higher education, the bureaucratic machinery of the federal government, and specialized financial entities that have profited handsomely, and sometimes corruptly, at the expense of both students and taxpayers. In an interesting twist on this theme, one of the case studies focuses on a major university, the Department of Agriculture, and the farm animals whose excruciating pain and suffering resulting from mistreatment that was inconceivable.

As Moldea describes in detail in Part I, student-loan companies have stolen up to one-billion dollars in illegal payments from federal taxpayer coffers, their crimes aided and abetted by leaders of the federal Department of Education. In Part II, Moldea exposes how under-regulated for-profit colleges soak up twenty-five percent of all federal student loans while spawning 55% of student loan defaults despite the fact that they represent a much smaller percentage of student enrollments. Since these colleges are totally dependent on these loans for profit, many have adopted rapacious practices to lure students into decades of heavy debt, leaving them near destitute with few repayment options. In Part III, Moldea concentrates on the University of Nebraska and the Department of Agriculture in their joint venture to conduct painful and wasteful experiments on cattle, hogs, and sheep and the ensuing cover-up attempt of the resulting carnage.

With each of these case studies, Moldea keeps the question of the whistleblower’s identity at the forefront of the reader’s mind. Moldea not only describes them in detail, he allows whistleblowers to speak for themselves, even including a casual conversation in Part IV of the book.

The courage, diligence, focus, and tenacity of the three whistleblowers that you will soon meet on these pages mirror our experiences with the thousands of whistleblowers with whom we have engaged through the years. While they represent a wide variety of backgrounds and also differ in terms of educational level, socio-economic status, and racial, ethnic, and gender identity, our clients share unique characteristics which are distinct and worthy of special mention. As you read, I hope you will agree with my observations.

* Whistleblowers almost always try to resolve problems internally before going public

As hardworking employees with high moral standards, whistleblowers almost always raise their concerns with their fellow employees or their immediate supervisors before going public. Before they blow the whistle more formally, they tend to first pursue the available institutional processes for identifying and reporting problems. It is only after becoming exceedingly frustrated with the failure of these channels that they consider going outside the organization. Again, the employees of conscience such as those discussed in this book each spent torturous years trying to challenge corruption by pursuing reform through internal means, before cooperating with the media as a last resort.

* Most whistleblowers would make the same choice to raise concerns publicly again, even if they did not prevail

Essentially, even if their careers are left in tatters and they find themselves unemployed or eventually employed in another field, they can claim pride when they look at themselves in the mirror in the morning or receive feedback from grateful victims of fraud who benefited from the disclosures.

As you read about the trio of whistle-blowing men of courage that Moldea has presented, I believe you will agree that each one is worthy of high praise and intensive study. Also interwoven throughout this book are descriptions of those intrepid reformers whose strong support has been critical in the defense of these whistleblowers and in ensuring that their disclosures have a nationwide impact.

David Halperin is one such person—a journalist, attorney, and public policy activist rolled into one superhero. For a decade he has helped to guide a national campaign to expose corrupt practices that appear endemic to for-profit higher education.

The alliance between whistleblowers and public interest activists is not just important, it is pivotal to ensuring that violations of public trust and institutional integrity come to light. But it is not enough. For truth and justice to triumph, there needs to be a much broader movement and social engagement to ensure that there is significant transformation.

For example, as Moldea chronicles, federal government bureaucrats at the U.S. Department of Education have allowed highly subsidized financial institutions to victimize students and to swindle taxpayers. For-profit educational institutions have essentially manipulated economically disadvantaged students into signing up for a lifetime of indebtedness without a quality education that could provide a means to escape their economic plight.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Office of Inspector General has essentially allowed a major university and the Department to escape responsibility for subjecting animals raised for food to inhumane, cruel, and inappropriate experiments. It is not enough to know about the corruption; rather we must act, each according to our ability and means of doing so.

In the early days of the movement in support of whistleblowers, we would often portray them as rugged individualists who alone would stand up, speak truth to power, and oftentimes prevail because truth matters. We called it “the power of one.” We now know that a more accurate assessment is that whistleblowers are a catalyst that will inevitably drown in the waves that they create unless reformers, public officials, elected representatives, academics, media and concerned citizens who care about truth, integrity, democracy, and transparency join in the struggle against corrupt institutions and leaders who profit from the status quo.